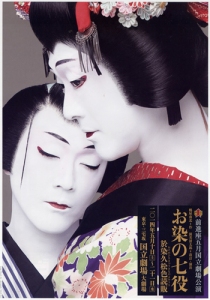

Among the traditional performing arts, kabuki is unarguably the most sensitive to the preferences of the audience and always ready to entertain its spectators with glamorous scenes and amazing stunts. “Seven roles of Osome” (Osome no nanayaku お染の七役) is just the kind of play that reflects these characteristics of the art of kabuki. This article is about the Zenshin-za performance of this play I saw last year in May at the National Theater.

Zenshin-za 前進座 is a theatre company active since 1931, famous for dealing with all kinds of artistic genres, from kabuki and modern theatre to film creation. “Seven roles of Osome” happens to be a very special piece in this company’s repertory. The story of two star-crossed lovers from Ōsaka first became a puppet theatre play and then began to be performed on the kabuki stage. The late Edo period (1603-1868) kabuki playwright Tsuruya Nanboku changed the location of the story from Ōsaka to Edo and thus adapted the play in order for it to succeed on the stages of Edo. Osome Hisamatsu ukina no no yomiuri, under its original title, become so famous that it was to be remembered by the more familiar title of Osome no nanayaku. It enraptured audiences both throughout Kansai and Kantō regions due to its highlight of hayagawari 早替わり – the lead actor perform seven roles at a time, using the trick of quick costume change.

However, the play stopped being performed in Tōkyō at the beginning of Meiji period (1868-1912). It was not until 1934, when it was revived by Zenshin-za, that “Seven roles of Osome” would be staged again. One of the initiators of Zenshin-za and a key-person in the Japanese theatre world of the 20th century, Atsumi Seitarō, had revised Tsuruya Nanboku’s original script by simplifying the contents. In addition, he was inspired in choosing the talented onnagata actor Kawarasaki Kunitarō V for the main role. The new “Seven roles of Osome” was a great success, and it soon began to be performed also on the mainstream kabuki stage by famous actors such as Bandō Tamasaburō and Nakamura Fukusuke.

The story itself is about Osome, the daughter of an oil dealer, and her lover Hisamatsu, the apprentice of her father. As they are not allowed to marry each other, the two agree to commit suicide together. Hisamatsu is actually a samurai by birth and if he could find the lost treasure of his house – a sword – he could restore the honor of his family. Starting from this plot, the story develops intricately throughout three acts and eight scenes, during which the lead actor plays a total of seven roles: Osome, Hisamatsu, Hisamatsu’s former lover Omitsu, Osome’s stepmother – Teishō, Hisamatsu’s younger sister – Takegawa, the geisha Koito, and Takegawa’s former servant – Oroku.

Right from the first scene, among the many people passing by the entrance to a temple, the audience (which is made up mostly of kabuki die-hard fans and connaisseurs) are able to recognize Osome, Hisamatsu, Takegawa and Koito appearing alternatively in the crowd. The second scene occurs indoors, but, in the same way, the actor playing Osome disappears through one side of the stage, only to appear again after no more than three seconds from the other side as Koito or Takegawa. The audience reacts each time with excitement, applauding the stunt. The most amazing act of quick costume change is certainly the last scene, where Osome and Hisamatsu meet on the Sumidagawa riverside with the intent of dying together. The two lovers meeting again after a long while – how does the actor manage to play the two roles – the man and the woman – at the same time? As you can imagine, the costume change occurs right in front of the audience. In the blink of an eye, with the help of an umbrella, the actor changes his appearance several times, convincing the spectators that both Osome and Hisamatsu are there present.

The lead actor in this Zenshin-za performance was Kawarasaki Kunitarō VI – “Yamazakiya”, as he is called by his fans. More than to show off the old stunt of quick costume change, he aimed at creating a distinct personality to each and one of the seven characters he played. This was especially visible in his interpretation of Oroku, who is the counter-image of Osome. While Osome is the gentle type of young woman, Oroku is rough and wicked, therefore the actor’s art had to cover the extremes of idealized beauty and realistic acting.

The emotional identification with the role one has to play and the actor’s effort “to become the character” have worked a long time as key tools in Western theatrical practices. As shown by plays like “Seven roles of Osome”, kabuki acting functions on quite different principles. In opposition to “heavy roles” which demand full emotional involvement of the actor, the structure of kabuki characters is lighter and more flexible, so that the actor is able to swiftly change roles. There is no way for “tragedy” to emerge as long as there is no aim for something like identification with the role. In other words, rather than the depth of emotion, kabuki’s charm lies in its lightness and its willingness to impress and entertain by all means.

The spectators who develop a taste for kabuki’s lightness remain devoted admirers of this stage art. They enjoy coming to see the same play with a different cast, closely observing each lead actor’s approach of the main role. The uniqueness of each actor’s art stands out especially through plays like “Seven roles of Osome”. To notice the differences between the actors and to be able to appreciate each one’s acting for itself is one of the things that kabuki fans find most delight in.

(*This is a slightly adapted version of the original article that can be read on my performing arts review column in Bungaku kingyo)